Mural by Jodie Herrera, Photo by Wade Roush

5.06 | 05.06.22 | Updated 05.12.222

Last summer, a pair of murals celebrating New Mexico's landscape, heritage, and diversity appeared in Albuquerque's historic Old Town district. The large outdoor pieces by muralists Jodie Herrera and Reyes Padilla—two artists with deep roots in New Mexico—brought life back to a once abandoned shopping plaza and became instant fan favorites, endlessly photographed by locals and tourists alike.

But in a January hearing, the the city’s Landmarks Commission, which is charged with preserving Old Town and Albuquerque’s other historical districts, said the murals were unauthorized and ahistorical and should be destroyed. Business owners and the arts community fought back, saying the commission’s ruling was capricious would amount to cultural erasure. Boosted by a flood of news coverage and public support, this coalition eventually won a new hearing before the commission.

In a city with such a rich multicultural heritage and a vibrant art scene, how did a disagreement about a couple of murals on private property escalate into a culture-war issue? Must communities make a binary choice between historical preservation and creative growth? Inside historic districts, which versions of history do we choose to preserve—and who gets to make these decisions?

Those are the big questions at the heart of this episode. We’ll hear from Herrera and Padilla, but also from small business owners trying to revitalize Old Town—and from a city official charged with trying to steer sensible enforcement of the city’s historic preservation ordinances. “Historic preservation is valuable and something we all respect, but it has to be parallel with a thriving contemporary community,” says Laura Houghton, who runs the Lapis Room Gallery in Albuquerque and selected Herrera and Padilla to paint the murals. The question for Albuquerque, and many other American cities, is how to balance both needs.

UPDATE: The second Landmarks Commission hearing on the future of the murals took place as scheduled on May 11, 2022, and the commissioners voted to let the murals remain. Listen to the end of the episode for a postscript about the hearing and local reaction to the decision.

Images

Resources Related to This Episode

Annalisa Pardo, City Landmarks Commission Rules New Old Town Murals Must Come Down, KQRE, January 18, 2022

Steve Jansen, ABQ Small Businesses Fight Commission’s Decision to Remove Murals, Southwest Contemporary, February 4, 2022

Alice Fordham, City Calls for Removal of Murals in Albuquerque Old Town, KUNM, February 8, 2022

National Trust for Historic Preservation, Preservation for People: A Vision for the Future, May 18, 2017

Albuquerque Landmarks Commission Staff Report on Request for Certificate of Appropriateness for 301 Romero Street (Plaza Don Luis), January 12, 2022

Albuquerque Landmarks Commission Supplemental Staff Report to January 12, 2022 Report, May 11, 2022

Her Strength: A New Mexico United Mural by Jodie Herrera (YouTube), New Mexico United, June 29, 2021

City of Albuquerque Arts & Culture Department

City of Albuquerque Planning Department

A Tale of Two Bridges, Soonish Episode 1.09, June 8, 2017

Notes

The Soonish opening theme is by Graham Gordon Ramsay.

All additional music in this episode is by Titlecard Music and Sound.

If you enjoy Soonish, please rate and review the show on Apple Podcasts. Every additional rating makes it easier for other listeners to find the show.

Listener support is the rocket fuel that keeps our little ship going! You can pitch in with a per-episode donation at patreon.com/soonish.

Follow us on Twitter and get the latest updates about the show in our email newsletter, Signals from Soonish.

Full Transcript

Wade Roush: You’re listening to Soonish. I’m Wade Roush.

Jodie Herrera: My mural is called “New Mexico Resilience,” and it's a cactus flower. Cactus flowers grow in the desert despite, and they blossom and they flourish despite their circumstances, like the New Mexican people.

Wade Roush: This is Jodie Herrera. She’s a mural artist based in New Mexico.

Jodie Herrera: And we've done that beautifully. And that's what it's supposed to encapsulate. And then also transformation. The butterfly. And how we've done that, how we've grown or how we've come to where we are today.

Wade Roush: This is an episode about butterflies and cactus flowers. But it’s also about public art, and what happens when art turns up in places where people may not expect it.

In the last few months, Jodie Herrera and another New Mexico muralist named Reyes Padilla have gotten caught up in a debate about the place of contemporary public art in a city that’s trying hard to preserve what’s left of its architectural history.

I’m talking about Albuquerque, New Mexico. That’s where I spent some time back in March. And that’s where the city’s Landmarks Commission is due to decide this month whether a pair of murals that Jodie and Reyes created last year in the city’s Old Town district should be destroyed.

The Commission ruled back in January that the murals violate city guidelines designed to preserve Old Town’s historic look and feel.

But that ruling got appealed, and then it got sent back to the Commission, and now they’re about to decide whether to affirm it or reverse it.

This whole story started out as a minor misunderstanding between the city and the new owners of a shopping complex called Plaza Don Luis over some paperwork that didn’t get filed in time.

Which is the kind of thing that usually wouldn’t get much notice beyond page three of the local newspaper.

But the Commission’s ruling in January escalated into a larger debate that’s drawn in the Albuquerque art community and business owners, along with the voices of more than fifteen hundred petitioners from all over the country.

KQRE News Report: News13’s Annalisa Pardo is live in Old Town tonight with that story. Annalisa.

[Annalisa Pardo:] Well, this is just one of the murals done by a local artist this summer that the city says needs to come down. But the owners of the plaza say they won’t paint over it without a fight. A petition with nearly 1,000 signatures to keep the artwork didn’t sway the city.

[City planner Leslie Naji:] Artistic wall murals were not part of the artistic or cultural style of that period.

Annalisa Pardo: The two sides walking the fine line on how to revitalize Old Town while preserving it.

Wade Roush: From one perspective, the question at stake is n square from the 1880s.

The question is also whether that space has room for diversity—in this case, for the expressions of contemporary artists of Latino and Native American heritage.

And of course all of this unfolding in a part of the world that was inhabited by native peoples for centuries before European settlers arrived, and that was claimed by Spain and then Mexico and then the United States, and where there are deep scars from centuries of conflict over how these multiple cultures should overlap and coexist.

So yeah, on one level it’s just a story about a couple of murals.

But I got interested because of what the story can tell us about the ongoing tension between preserving the past and creating a future with room for everyone. And about how city government functions and sometimes malfunctions. And maybe about how communities can get better at deciding together what kinds of values they want to embed and express through their built environment.

If the Landmarks Commission does decide that the murals have to be painted over, they’ll be acting in defense of some seemingly sensible policies that aim to keep Albuquerque connected to its history.

But the reality is, destroying the murals would be seen by the arts community and the Latino community of Albuquerque as an act of literal cultural erasure.

A couple of weeks ago, one of my favorite tech writers, Charlie Warzel, was tweeting about all the drama about whether Elon Musk was going to buy Twitter. I had to laugh when Charlie wrote, quote, “The rule of being alive right now is to not bet against the dumbest possible outcome.”

Well, turns out Charlie was right about Twitter.

And my personal feeling is that if the Albuquerque murals get destroyed, that will be the dumbest possible outcome of this case.

But that hasn’t happened yet. There’s still time to talk it through. And that’s what we’re going to do today.

Before I dive in, just a side note. This story will make a lot more sense if you’ve seen the actual murals. If you live in Albuquerque, you can drive down to Plaza Don Luis in Old Town and check them out yourself. If you don’t, just go to our website, soonishpodcast.org, and check out the web post for this episode.

Okay, let’s start by meeting the instigator of this whole story.

Jasper Riddle: Yeah, so my name is Jasper Riddle. I'm the owner of Noisy Water Winery. We're based out of Ruidoso, New Mexico. I went through K through 12 in Ruidoso so I'm very much a New Mexican.

Wade Roush: Ruidoso is in central New Mexico. and it’s named after a creek that ran through the town called the Rio Ruidoso, which literally means Noisy River or Noisy Water.

Riddle wanted to open a place in Old Town where he could serve and sell his wines.

For decades there was a law on the books in Albuquerque against package sales of alcohol in the Old Town neighborhood. Riddle worked with his fellow wine growers and brewers to get the law changed.

And that cleared the way for local wineries and breweries to bring some new businesses to the district. Which it definitely needed.

Rosie Dudley: Soon after I moved back in 2018, I went and did my Christmas shopping in Old Town and had no problem finding a parking space. It was pretty empty.

Wade Roush: This is Rosemary Dudley, who goes by Rosie. She’s an urban planner and she’s the chair of the Albuquerque Landmarks Commission. We’re going to hear a lot more from her later in the show.

Rosie Dudley: And I was really struck by that. Like, where are the shoppers? It is Christmas time. And this is pre-pandemic. And I think whatever we can do as city representatives and leaders to encourage positive investment in Old Town, the better.

Wade Roush: So here’s the deal with Old Town.

It’s the original site of the Spanish village of Albuquerque, which was founded in 1706 by the governor of a province of the Spanish Empire called Santa Fe de Nueva Mexico.

The village was built in a grid around a central plaza or park, and the street layout is pretty much the same today.

On the north side of the plaza There’s a beautiful 18th-century church called San Felipe de Neri, and on the other three sides there’s a mix of wood and adobe buildings with covered sidewalks. Most of them have been turned into shops and restaurants.

T here’s also a storefront that serves as the headquarters for a business that takes people on Breaking Bad bus tours.

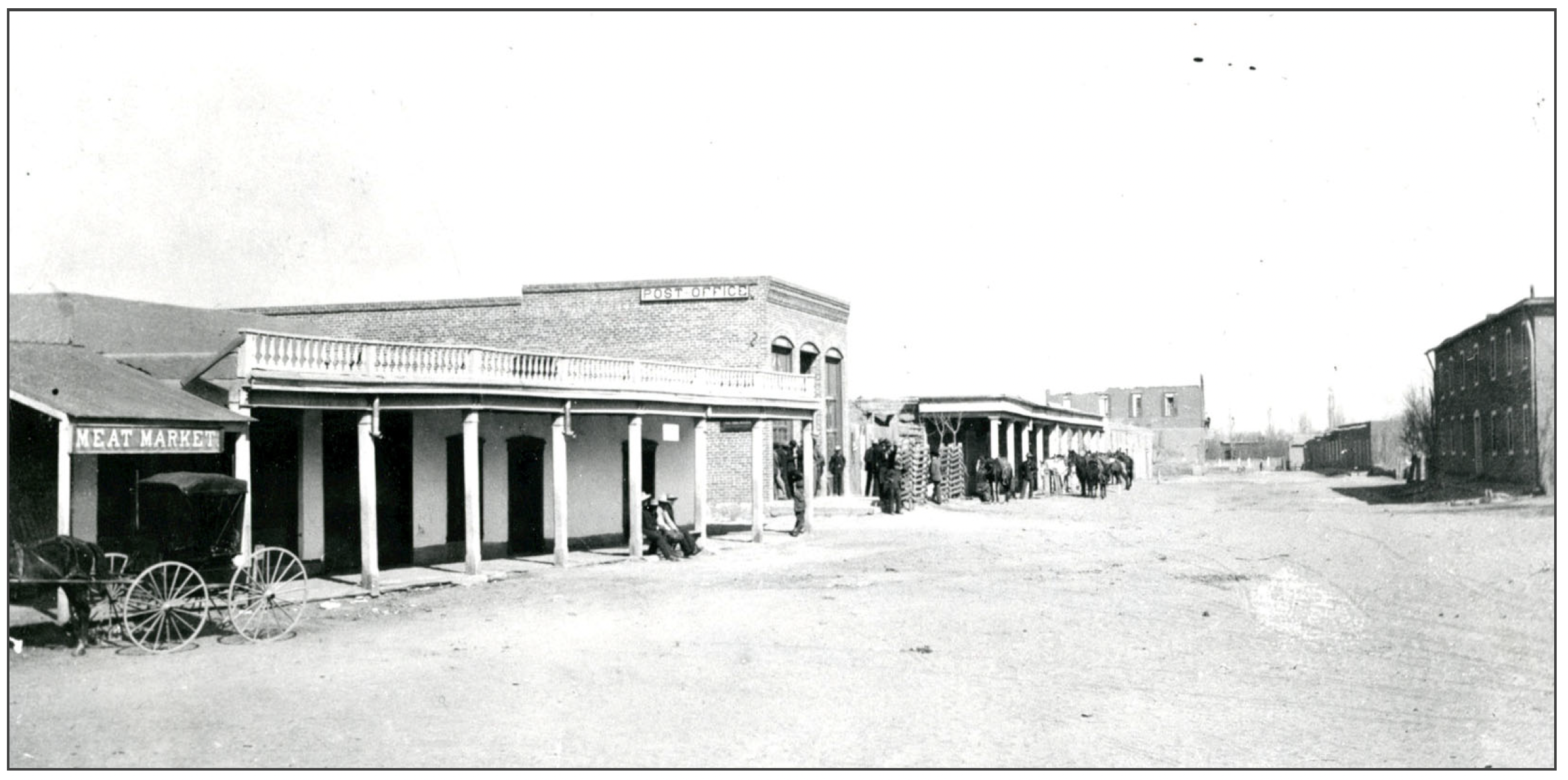

It’s a fun place to walk around. But as a functioning town center the area probably peaked around 1880.

That’s when the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway reached Albuquerque.

They built their depot two miles to the east.

The neighborhood around the depot became the city’s new downtown, and even today that’s where you find all the city’s big office buildings.

Which meant Old Town went into a kind of sleepy retirement that lasted almost all the way up to the present.

So when Jasper Riddle decided to locate in Old Town, he knew he’d have some work to do to make sure his business thrived.

He started by buying an old brick building west side of the main plaza. It dates to 1893 and locals refer to it as the Basket Shop.

At the same time, Riddle took over an adjoining structure called Plaza Don Luis.

Jasper Riddle: Found this plaza. And I thought, man, this is an amazing opportunity. However, it's way too big of a project for me to take on by myself. Got a good friend of mine together and a couple other folks and we purchased this property. But with the understanding that we are going to work with local wineries, breweries, you know, craft industry, supporting nonprofit groups to really try to build this kind of craft culture in Old town.

Wade Roush: Now, Plaza Don Luis is a two-story building in what’s called the Territorial architecture style. It wraps in a U shape around a central courtyard. And it was originally built in 1993 as a shopping complex. It’s got 32,000 square feet of retail space.

But by the late twenty-teens it was pretty much empty.

Reyes Padilla: There was a period of time where I just walk my dog down there and I wouldn't see a soul.

Wade Roush: That’s Reyes Padilla, one of the artists at the center of the controversy. He lives in the neighborhood. And he says of all the places around the Old Town, Plaza Don Luis was probably in the worst shape.

Reyes Padilla: You know, there was trash. There was a lot of stuff that was kind of shocking for the Plaza. But I remember just wandering, even going up and down the stairs onto the balconies, and it was like an absolute ghost town.

Wade Roush: So everybody seems to agree that Old Town needed a facelift.

Jasper Riddle turned the Basket Shop into a beautiful tasting room for Noisy Water.

And he joined with a group of small business owners to give Plaza Don Luis a makeover too.

The idea wasn’t just to fix up the place and fill it with new businesses, but also to give it a sense of place so that tourists and shoppers would want to hang out there.

That’s where another Ruidoso native named Laura Houghton came in.

Laura Houghton: I am the owner and director of Lapis Room, which is a contemporary art gallery in the Plaza Don Luis. So my background, I've been in museum settings, I've been in public art settings, nonprofits for many, many years. And I came into this community to first, well, to open the art gallery, but also the new ownership of Plaza Don Luis enlisted me to make it a compelling attraction. It was an entire community that valued the arts. They knew they wanted it to be a vibrant art center, but also to be the stage for music, for entertainment. So those were values that I also had, and I had experience coordinating things like that.

Wade Roush: As part of the transformation of Plaza Don Luis, Jasper and Laura and the other business owners agreed to pitch in to commission a couple of large murals.

One would go on the side of a small building at the back of the plaza that houses a pair of public restrooms. And the other would go on a rear wall of the complex, next to a staircase that leads visitors up to the second-floor balcony.

Houghton agreed to help find the right artists for the job. And she quickly identified her two favorites.

Laura Houghton: There are so many wonderfully talented people of the area. But really, Reyes and Jodie struck me very early on as two significant artists. They're prolific. They have murals throughout the city. They've been commissioned by the city itself to create significant pieces throughout. I think their rich family history is so deeply rooted in New Mexico on both sides.

Wade Roush: Now, Jodie is actually the first person I interviewed about this whole story.

Back in March, after a week in Santa Fe, I had a whole morning free to poke around in Albuquerque.

A friend who knows Jodie told me that I should look for an amazing piece of art she painted in the city’s modern downtown to help promote Albuquerque’s soccer team, United.

That mural shows an athletic-looking woman flexing her bicep in a deliberate homage to the famous Rosie the Riveter poster from 1943. I’ve put a picture of that on our website too.

Anyway, after I found the soccer mural, I ended up wandering a couple of miles down the road to Old Town. At that point I desperately needed coffee and something to munch on, so I wandered into Plaza Don Luis. I found a bakery at the back of the Plaza called the Flying Roadrunner where I grabbed coffee and a quiche.

And that’s when I noticed Jodie’s signature on another mural, this one showing a desert scene. And not far away, spanning two floors of the plaza building, was another much more abstract mural.

I took a picture of Jodie’s mural and texted it to my friend in Santa Fe. And she texted back to tell me that it was slated for removal, because it supposedly conflicted with the historical character of Old Town.

That seemed pretty odd to me, especially since it was clear that Plaza Don Luis itself is pretty new. I needed to find out more. So after I got back home to Boston, I reached out to Jodie herself.

I learned that she had just finished the mural in September. And before we got into why the two murals are in jeopardy, I asked her to talk about her work as an artist, and what ideas Laura Houghton’s invitation inspired.

Jodie Herrera: I grew up in Taos, New Mexico, and I was born in Albuquerque. My family has been here for hundreds of years, so deep roots. When I was young, very young, I always knew I was going to be an artist. My mothher's a full time artist and has been for many years now. So I’m really proud of her. And yes, I grew up really supported. I even had a wall in my family home that I would scribble on. I guess you would call that my first mural that I ever did. And when I became a young adult, I guess in my late teens I got really into hip hop culture and graffiti art, and so I started doing large scale through the graffiti art scene in Albuequerque was something that really opened my eye up to the possibilities of creating large scale.

Wade Roush: And when Laura approached you about the mural for Plaza Don Luis, did she give you like any ideas or any constraints or suggestions? What was your thinking process about what did you want to convey in that space?

Jodie Herrera: So when she asked me to do it, she trusted that I would represent New Mexico. that's one of the reasons why I really was I felt really honored to create it, was because I felt like she did her homework. She wanted to find an artist that is from Mexico, local and also loves New Mexico. And she did that with Reyes as well, which I thought was really great. But yeah, when she asked me to do it, she was just very, she just trusted my artistic direction. And that's always kind of like a dream job for an artist to be able to create something that is and doesn't have a lot of boundaries or creative dictation or anything like that.

Wade Roush: I'd like to ask you to describe it, like just kind of give a visual tour of the piece.

Jodie Herrera: So in the piece “New Mexico Resilience,” you'll see to the left. The first thing that is kind of the main subject is cactus flower in full bloom. And the full bloom of the flower represents the knowledge of the ancestors. So our instincts to bloom, that's said to be the knowledge of our ancestors, of our past before. And then there's buds at the bottom of the cactus blossom, and those are to represent the youth. And so for both the past and the present and also there's going to be a line that goes horizontally across the whole work, and it has geometric figures of upside down triangles and right side triangles to represent duality. The female and the male are the good and the bad. Positive and negative. And then to the far right you're going to see a butterfly, mariposa. And this mariposa is known to migrate south and up north through New Mexico. And so knowing that transformation has no boundaries and also the beauty of transformation.

Wade Roush: Mm hmm. So if somebody looked at New Mexico Resilience, the piece in Plaza Don Luis, and saw kind of a line between graffiti art and that mural, they wouldn't be wrong, right? There are kind of like flavors or aesthetics in common between what we think of more as graffiti art and your piece, which is also pretty photorealistic.

Jodie Herrera: I think that's a really great question. I am a byproduct of the culture that I was born from, right? And so that's a part of my history. And so my work is always going to be always a conversation to that. Being the fact that I use spray paint as a medium because I learned within, I learned how to create large scale using spray paint. Right. And that's that's directly from graffiti culture. So yeah there’s always going to be elements of that. But that doesn't take away from the art itself. Sometimes when you're not really educated on the influence, the positive influences of graffiti culture, that seems like it could have like a negative connotation, but it actually doesn't. It's actually just an homage to the history of that. And so really, if I didn't have that, I wouldn't be where I am today and I wouldn't be able to create and do the work that I can do at this point.

Wade Roush: Later I got in touch with Reyes Padilla. And we had a similar conversation about his roots and his unusual method of working.

Reyes Padilla: I was born and raised in Santa Fe, New Mexico. I am a visual artist. I primarily work in like abstract and muralism . I focus on synesthesia, which means I can see sound. And I paint basically what I am seeing while I'm listening to music. So a lot of my work is inspired by sound. I've been a full time artist for almost seven years. [00:05:49] My first mural, the first public mural really was in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in a little borough called Braddock. And I've had work go all over the country to multiple parts of the world. Mainly, I've done work in New Mexico.

Wade Roush: Do you listen to music mostly while you're painting because the sound is more organized in a way. I'm just kind of speculating here, but like, is it easier to paint, you know, a rap song than it would be to paint a traffic jam, for example?

Reyes Padilla: Oh, yeah. Yeah. I mean, and I like I like painting the, like, hip hop because there's a repetitive beat to it and it's, it's easier to lock into a certain visual. But yeah, I mean, I can paint to a traffic jam or I've done pieces that are based in silence and meditation because there's still a visual element to that. So, you know, I definitely tap into any kind of sound that could be. But, you know, personally, I'm just painting to whatever my mood is at that time.

Wade Roush: Let’s zero in on Plaza Don Luis. Just so that people have a little better understanding of what this mural looks like. Like, what colors and forms did you use?

Reyes Padilla: I would describe it as like responding to the architecture, using colors that reflect the New Mexico landscape. So I wanted something that I mean, it really is very much myself, but it's kind of like a self-portrait in a way. But it also just like represents the way I feel about New Mexico, I wanted people to to see these colors that emphasize the New Mexico landscape and almost blend in with it…So the colors I used, black turquoise, metallic gold and white. The turquoise and the gold. Definitely emphasizing the sky and and the sun, which is New Mexico in a nutshell, but also the sand. And then we have very little light pollution here, so we get absolute darkness as well. So that gradient reflects the nature of New Mexico.

Wade Roush: What kind of feedback have you gotten about the mural?

Reyes Padilla: I've gotten amazing feedback. It's been one of the more noticed pieces that I've done. People are very excited that it's in Old Town. While I was painting it, you know, people who were around for the tourism season were really cheering it on. They were excited about it. They were taking pictures. So yeah, I've heard nothing but positive feedback on my end. I don't know if anyone would tell me directly if they they didn't like it, but yeah, it's just I mean, both murals in general have gotten a huge amount of praise and especially when people know that there's a conflict with them. People have been extremely vocal in their support to keep the murals.

Wade Roush: So, back to the conflict.

In January, Reyes and Jodie found out that the Landmarks Commission wanted both of their murals removed.

And Jodie says it was hard not to take that decision personally.

Jodie Herrera: What they're doing is in order to try to preserve this façade. It feels like reversing time, like we're we're going backwards and we're not validating the rich art culture, which we've grown from the roots up and really nurtured. And here we are, because of this bureaucratic misunderstanding, n ow we're sacrificing something really important that is going to really upset the public. It's going to upset me and Reyes and, of course, the owners of Don Luis. But if anything, that reflects…how we treat our artists and how we treat our culture, the people that are really fighting to preserve our culture and really trying to put our state on the map…by representing who we are and putting our work out into the world. And then, you know, this is how we're treated in our backyard.

Wade Roush: This is where we need to talk about the bureaucratic misunderstanding Jodie just mentioned.

Back in early 2021, when the renovations at the Basket Shop and Plaza Don Luis were about to begin, the plaza’s owners and architects met with City Planning staff and with officials from Albuquerque’s Department of Arts & Culture.

Riddle says they’d read the historic preservation guidelines for the Old Town, and there wasn’t anything in them that specifically prohibited murals.

But they still wanted to make sure their plans were kosher.

Jasper Riddle: Yeah, to the mural point directly, actually it’s not clearly outlined. They don't describe murals and that's the big thing. We actually had reached out to arts and culture from the city. We said, what permit do we need to do a mural? And they said, there's no permit needed to install a mural on private property. Go ahead. So at that point in time with Landmarks not defining the exterior painting or murals and what we understood and what our architect understood, we felt there was a green light and that there was no guidance or anything otherwise stating that this was not allowed.

Wade Roush: So they went ahead with the renovations, and commissioned Jodie and Reyes to paint the murals.

It wasn’t until after everything was finished that Riddle learned that there’d been a huge communications breakdown.

Plaza Don Luis lies inside a Historic Preservation district called HPO-5, which is the same district governing the San Felipe church and the central plaza.

And within the boundaries of those districts, building owners have to apply to the Landmarks Commission for something called a Certificate of Appropriateness before they can modify any structure, even if it isn’t a historic or so-called “contributing” structure.

Riddle says no one in the Planning Department or the Arts and Culture Department or the Landmarks Commission ever told him about that requirement.

Jasper Riddle: Here's the thing that baffled me. Our architect, who built the Plaza in 1993, was recommissioned by us on this project. He spoke to Landmarks about every single change we were making, every single thing we were doing. And we had we had verbal go-ahead from the planners at Landmarks on everything we were doing . For us, it was shocking when they reached back out and said, you need a certificate of appropriateness. Within 24 hours I submitted saying, look, I'm sorry if I missed a step. Don't be upset at us. We were trying to do everything. We thought we were in full communication.

Wade Roush: Riddle went ahead and applied for a Certificate of Appropriateness retroactively.

And that’s the request the Commission decided on in January. They voted four to two to approve almost all the changes Riddle and his builders had made, except for two things.

The majority of the commissioners felt that a wrought-iron railing that Riddle had installed on the Basket Shop’s front porch was inconsistent with the building’s historic look.

And the same 4-2 majority was unhappy about the murals. Their decision said that the murals are, quote, “not in keeping with the historic integrity and sense of place of Old Town,” unquote.

As a condition for getting the other changes certified, they ordered Riddle to remove the murals and the railing

Chairperson Rosie Dudley was in the minority on that decision. Here’s her account of the meeting.

Rosie Dudley: The discussion about about the murals, I think everyone who spoke on the commission about the matter were pretty clear that they had no issues with murals as an artistic expression, that the quality of the murals were not in question, and that they are not opposed to murals throughout other parts of the city. But the argument was that Old Town, given its 1880s to 90s origins, is not an appropriate place to have wall murals like that, that the only types of paintings on buildings that occurred during that time were signage as paintings that were advertising, you know, like buy your sandwiches here, kind of signs. I've appreciated Jodie's work throughout the city. There's numerous ones in downtown that I see on a regular basis. So, you know, I don't think anyone had intention to to say these murals aren't high quality. But the argument against it was that these are not appropriate to the 1890s and 1880s.

Wade Roush: I can hear you kind of bending over backwards to be to represent the commission here and to talk about the general decision. So you're not necessarily speaking for yourself. You’re speaking for the commission in describing the outcome.

Rosie Dudley: Yes. So both myself and one other commissioner are not in agreement that these murals needed to be removed from the property. And, you know, if you look at this in the big picture, there are a lot of aspects in Old Town that are compromising its historic integrity. You know, it could be something as silly as a bunch of plastic displays that are up at Christmas time, you know, hanging off the side of buildings or on their portals or as serious as buildings in in poor condition with broken windows and debris collecting. You know, there I think there are there are a lot more better ways where we could focus our energy than to have buildings that had have brand new murals painted on them, have those murals removed. I think they are not hurting Old Town and they are not hurting the character of Old Town to warrant their removal.

Wade Roush: Like everybody else I interviewed for this story, Rosie Dudley was born and raised in New Mexico.

In addition to her volunteer post with the Landmarks Commission, she works as a planner for the University of New Mexico, where the central campus also adheres to the Pueblo Revival style, and has eight buildings on the National Register of Historic Places.

That means she’s deeply familiar with conversations about how to preserve historical resources while still serving the community’s needs.

Wade Roush: How would you describe the intentions behind the design guidelines for HPO-5, for the Old Town District? Like, what are you trying to accomplish there? Is there an era you’re trying to evoke, or an aesthetic that you’re trying to preserve?

Rosie Dudley: Yeah, well the big picture for Albuquerque and our historic resources, just to give you context, we as a city have lost countless resources, historic resources, buildings, entire neighborhoods are no longer standing. And there are a lot of good books that document that, that loss structures. And so that's where a lot of people who care about historic structures are coming from, is the concern that let's not do that again, let's not continue to tear down amazing architectural gems and leave parking lots in their place for decades. And that is that is, those are still evident across the city. Old Town has a really interesting history in that what you see today in Old Town, it was not always looking exactly like that. There was a time very soon after its origin, and it wasn’t originally called Old Town, where the adobe and wood portals and whatnot were masked with a more Victorian look, like you would see in historic New Orleans, for example. And then was returned to more of the Spanish Pueblo Revival style that you see today. So this debate about what Old Town should look like is longstanding. But I think to go back to your question, the intent of these guidelines is to ensure that Old Town remains a cultural and historic resource for the city.

Wade Roush: I've talked to people who have it in their minds that the city basically wants to see the place look the way it did roughly between 1880 and 1912 when New Mexico became a state. So is it fair to say that that's the the era that you're looking to sort of evoke or emulate?

Rosie Dudley: Right. The 1880s and 1890s, that era.

Wade Roush: After the historic preservation movement swept across the United States in the 1960s, basically every big city set up a Landmarks Commission or something like it with special rules that constrain property owners.

That’s certainly true in Santa Fe, about an hour north of Albuquerque.

Santa Fe has managed to hold on to more of its historic buildings than Albuquerque, in part because it enacted a historic district ordinance in the 1950s, years before most other cities.

Reyes Padilla grew up in Santa Fe, and he points to one longstanding criticism of historic districts, which is that they often seek to preserve just one moment in history, or one version of history.

And often, it’s the one visitors expect to see.

Reyes Padilla: You start going down this slippery slope of okay, what is appropriate and who's making these decisions, where are they from, what do they, you know, what's their interpretation of what this this part of town is supposed to look like from this date to this date? The part that's being brought up about things not adhering to the time period between I believe it's like 1880 and 1912. I don't buy any of that because you walk around old town and you see digital parking meters, you see parking lots, you see you see other artworks that are not relevant to that time period. So in that aspect, personally, it just felt targeted. And I think I think there's a balance between respecting the past and growing from the past as well. These dates, 1880 and 1912, don't represent New Mexico. Those are very odd dates to choose. It’s not like the world was stagnant here.

Wade Roush: When I talked with Jodie, she also sounded frustrated that the Landmarks Commission’s choices seemed so arbitrary.

Jodie Herrera: The approval of what they feel is aesthetically appropriate for Old Town is very subjective. So they're saying that murals didn't exist during the time period, that they are trying to, I guess, reflect or mimic in Old Town, which is untrue because Old Town murals are the oldest art form in history and largely existed everywhere that you can think of. You can go back to petroglyphs if we want to bring evidence to the table.

Wade Roush: It’s no coincidence that Jody mentioned supporting evidence, because that’s actually what the next phase of the case is about.

After the Landmarks Commission declined to approve the murals back in January, Jasper Riddle and the other owners of Plaza Don Luis appealed the decision.

In Albuquerque there’s a city official called the Land Use Hearing Officer or LUHO who reviews these kinds of cases. In this case, the LUHO was a city attorney named Steven Chavez. And Chavez determined that the Landmarks Commission had ruled on the murals without sufficient evidence.

He remanded the case back to the Landmarks Commission, which basically means they have to start from scratch on Riddle’s request for a certificate of appropriateness.

Chavez said both sides need to move beyond subjective opinions and bring objective facts to the case.

He said the majority on the Landmarks Commission has to prove its contention there are rules prohibiting murals in Old Town and/or that the murals are incompatible with the preservation guidelines. He also said the commission can’t appear to be acting out of retaliation for the late paperwork.

At the same time, the owners of Plaza Don Luis have to bring more evidence that the murals are appropriate, that there’s precedent for having contemporary public art in Old Town, and that they altered the property as little as possible during the renovations.

All of that is what’s supposed to be discussed at the May 11 hearing.

It’s a virtual public meeting on Zoom. I’ll be following along and my plan is to update this episode after the hearing to let listeners know where the story stands.

I can make one prediction with confidence. If the Commission doesn’t reverse itself and the murals have to be painted over, there are going to be a lot of very sad and angry people in Albuquerque.

Reyes Padilla: I think it would just cause more of a mess than any of the publicity it's gotten so far. The community is very supportive and outspoken, and I think it's kind of a slap in the face to a lot of people who have kind of gone on their own mission to to find ways to support these murals.

Jodie Herrera: If these murals are erased, I think that there's going to be a huge backlash and they're going to have to deal with that. The backlash alone will be a lesson learned for the for the Landmarks Commission. And then they’ll really understand what they’re doing. I don't think they understand at this point what they're erasing.

Laura Houghton: Historic preservation is valuable and something we all respect and but it can't be it has to be parallel with a thriving contemporary community, and that's part of it. So you can't have one or the other, if the contemporary community isn't thriving in the district that is looking to be protected.

Wade Roush: If there’s one good outcome from all this, it may be that more people in Albuquerque are paying attention to the work of the Landmarks Commission. That’s a point I heard from both Jasper Riddle and Jodie Herrera.

Jasper Riddle: I think, you know, this is the point in time where I said to the people around me, you know, get get involved, be a part of the change we need to help steer this. You know, there are open seats on the Landmarks Commission right now. So I would encourage, for people that are, you know, have new ideas and a new mindset to get involved.

Jodie Herrera: I do have compassion for people in that position that are they're put in a position to make a decision about a culture that they know little about or they really have nothing to do with. And they are expected to be able to make these decisions. Right. So I have compassion for that, but I hope that it was a learning opportunity and there was a moment that we could just take a moment of pause and be like, okay, maybe we should actually have people…that have an arts and cultural background in these positions on these boards so they can actually be qualified to make the decisions at hand, because I just don't think that they were in the place where they could they could do that.

Wade Roush: From talking with Rosie Dudley at the Landmarks Commission it was clear to me that Jodie and Reyes already have at least one ally on the commission.

Rosie Dudley: Old Town shouldn't just be kept in a little box preserved behind glass. It needs to continue to be a living and breathing part of our city in order to survive and to have meaning for this generation and future generations. So while I think the majority of the old town guidelines are upholding that integrity of Old Town, we do need to be thoughtful about not making them too prescriptive. So they're deterring new business and and new energy and culture from occurring.

Wade Roush: One of the questions I've been asking everybody I talked to is like, if you kind of project forward a few months to the future and maybe the hearing is over, it's past May 11th and there's been a decision rendered one way or the other. Can you imagine this controversy leading to perhaps a thinking through of the way that these conversations run in Albuquerque like. In an ideal world, would you come out of this having a better understanding of the community of art, of artists and creators and the contributions they want to make to public art and how they want to feel included in an even in a historic district like Old Town. Can you imagine finding ways to maybe fill out the membership of the commission and, like, fill those vacant seats and get more different perspectives represented on the commission? Can you imagine doing a better job of making sure everybody understands the guidelines and the intentions behind them and that that, you know, nobody stumbles into this kind of controversy in the future. It feels like there are all sorts of ways you could improve the process. And maybe this one outcome of all of this could be some conversations around that.

Rosie Dudley: Yes, yes, yes is my answer to all of those things. I could imagine those would all be beneficial outcomes of this unfortunate issue. I think in particular from a city perspective, just making that process as clear as day for new property owners. It's a waste of taxpayers dollars and everyone's time to go through these hearings and then have the LUHO and the r appeal. Not to mention, you know, how upsetting it is for the property owner and the artists. So I think an improved process could benefit us all. So I'm glad that this decision isn't final. And I hope that we can come to one that meets everyone's needs.

Wade Roush: There’s an organization in Washington called the National Trust for Historic Preservation. It was founded by Congress in 1949 and it works to identify and protect historic landmarks around the country.

In 2017, to mark the 50th anniversary of the National Historic Preservation Act, the Trust came out with a report that I think should have gotten a lot more attention.

It’s called Preservation for People.

And it acknowledged that for a long time, the preservation movement’s highest priority was simply to halt the spasm of so-called “urban renewal” that led to the demolition of so many old neighborhoods.

But the report argued that we’ve grown past that era. The challenge. now isn’t just to keep historic places intact. It’s to keep them, quote, “alive, vibrant, and responsive to contemporary needs through continuous use and reuse.” Unquote.

Every local community needs to figure out what being responsive means for them.

And I think folks in Albuquerque are looking for aliveness and vibrancy in their historic districts.

Which is why the dumbest outcome of all would be to erase Reyes Padilla’s abstract synesthetic designs and Jodie Herrera’s cactus flowers and butterflies.

That’s it for this week’s episode.

If you want to listen in on the Landmarks Commission hearing on May 11th, it’s a public meeting, so I encourage you to do that. I’ll post the time and the Zoom link on the web page for this episode at soonishpodcast.org.

Soonish is written and produced by me, Wade Roush.

Our intro music is by Graham Gordon Ramsay.

The outro music and all the other music in this episode is from Titlecard Music and Sound in Boston.

We’re on Twitter at soonishpodcast, and at our website, soonishpodcast.org, there’s transcript of this episode and links to more coverage of the Old Town mural controversy and the art scene in Albuquerque.

Special thanks to Ellen Petry Leanse for introducing me to Jodie Herrera, hosting me during my visit to New Mexico, and helping me settle on a title for this episode.

Soonish is a proud founding member of Hub & Spoke, a nonprofit collective of indie producers making some of the smartest audio stories out there.

And this week I want to shine a well deserved spotlight on Erica Heilman, the producer of a Hub & Spoke show called Rumble Strip.

Erica found out recently that she’d been nominated for a Peabody Award in the radio and podcast category, for her episode “Finn and the Bell,” and if you haven’t heard it yet, you need to get yourself over to rumblestripvermont.com to check it out.

It’s story about a young man named Finn Rooney and how his suicide in 2020 transformed the small Vermont town here he lived.

It’s a devastating story and yet it’s somehow uplifting at the same time.

Roman Mars from 99% Invisible says that it’s quote, “probably in contention for the best audio documentary I’ve ever heard.” Unquote.

The Peabody is one of the nation’s top broadcasting awards, and Rumble Strip was the only independent podcast to be nominated.

We couldn’t be more proud of Erica, and I just want to say please, go listen to “Finn and the Bell” and then check out Erica’s entire archive.

That’s it for now. Thanks for listening, and I’ll be back with more episodes… Soonish.