3.04 | 5.14.19

The adjective “visionary” gets thrown around a lot, but it’s literally true of Chesley Bonestell and Arthur Radebaugh, the two illustrators featured in this week’s episode. Both used their visual imaginations and their artistic talent to bring engaging, influential depictions of human space exploration and our high-tech future to magazine and newspaper readers in the 1940s, ‘50s, and ‘60s. And both are the subjects of recent documentary films.

Chesley Bonestell was born in San Francisco in 1888, survived the earthquake and fire of 1906, and went on to become an accomplished and high-paid architect, artist, Hollywood matte painter, and illustrator of book and magazine articles. From the mid-1940s onward, he specialized in painting stunning views of space vehicles and views other otherworldly locations like the Moon, Mars, and the moons of Jupiter and Saturn. He lived to see humans set foot on the Moon in the 1960s and visit the gas giants via robotic probes in the 1980s, finally passing away in 1986.

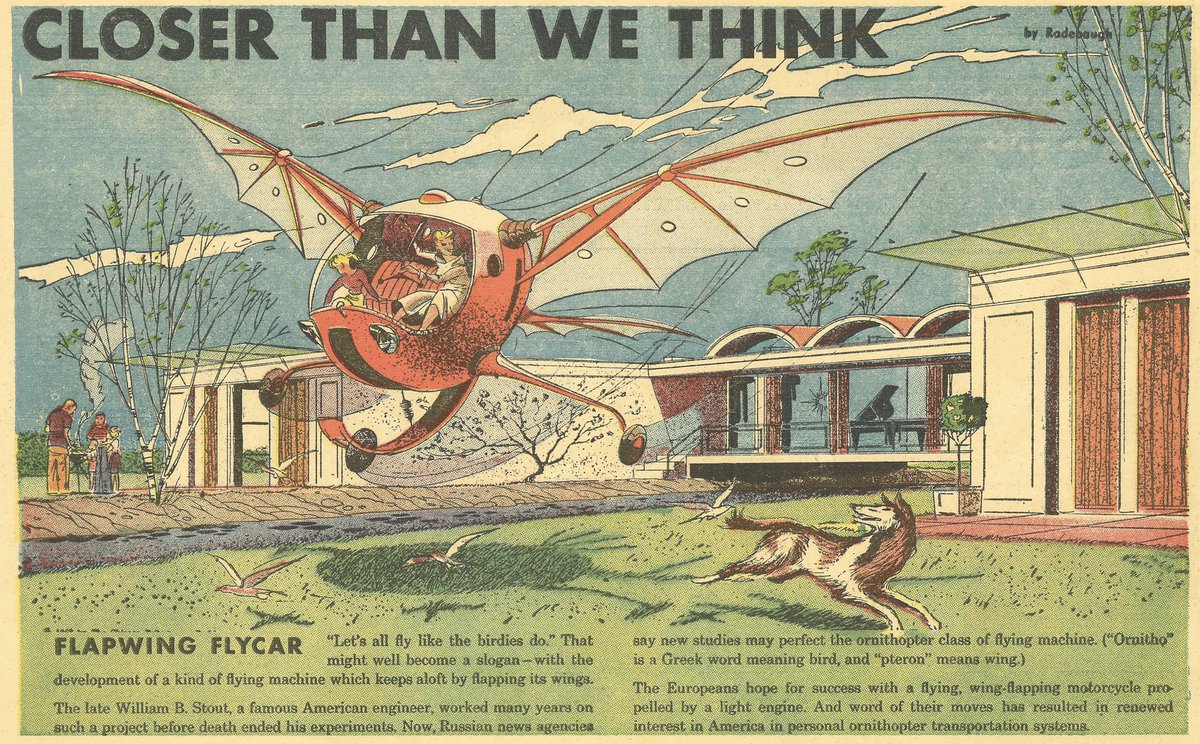

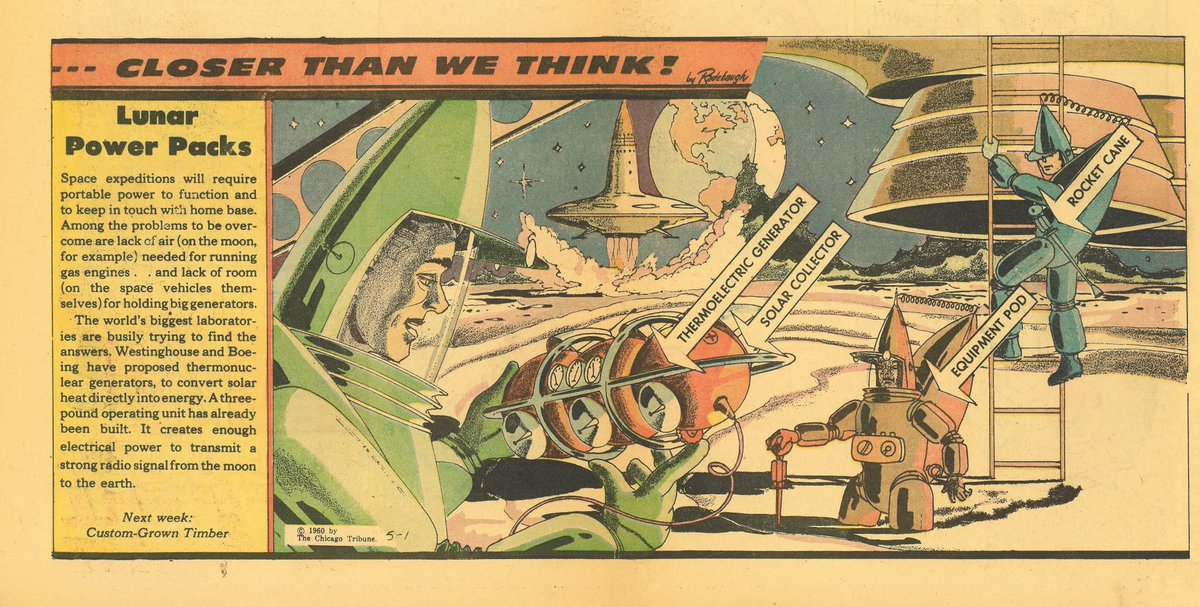

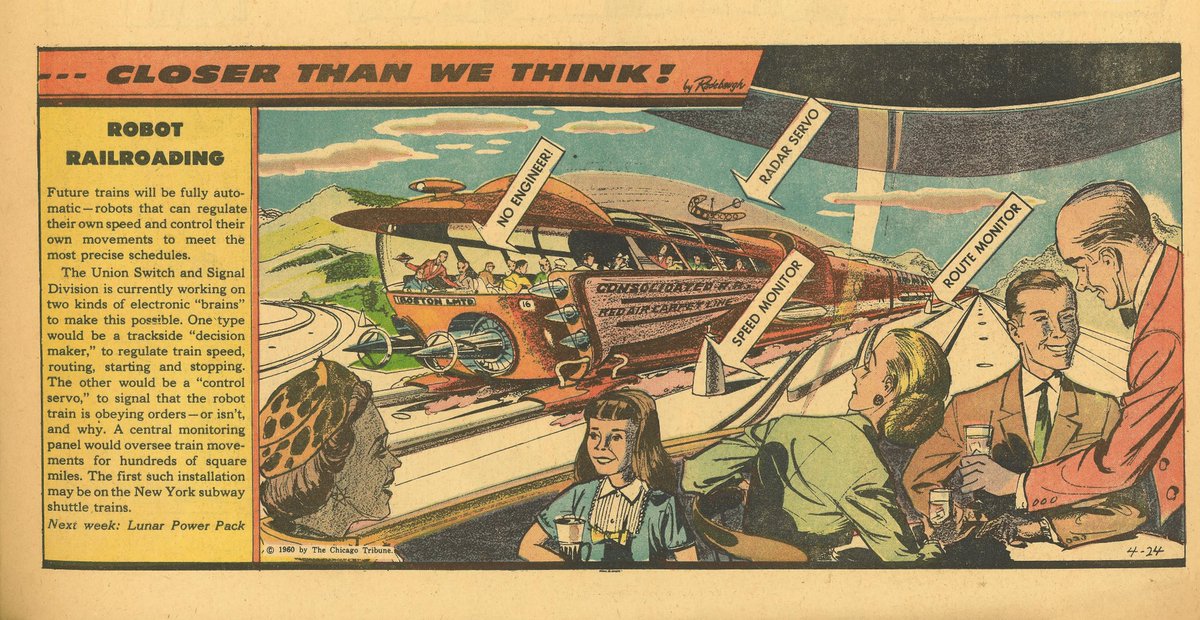

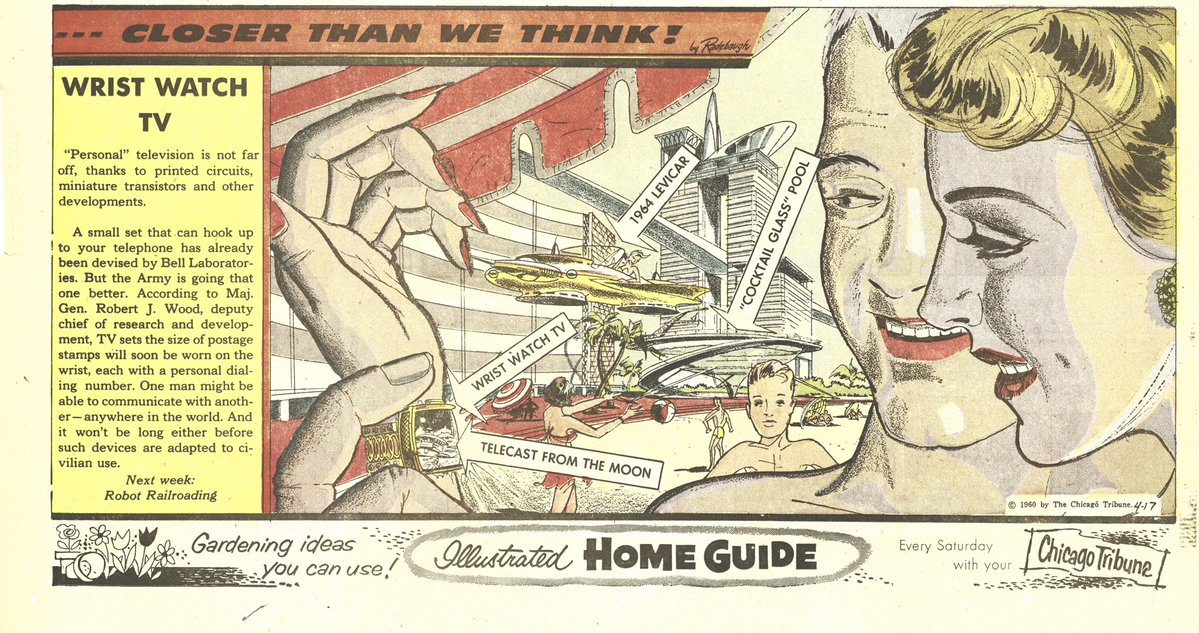

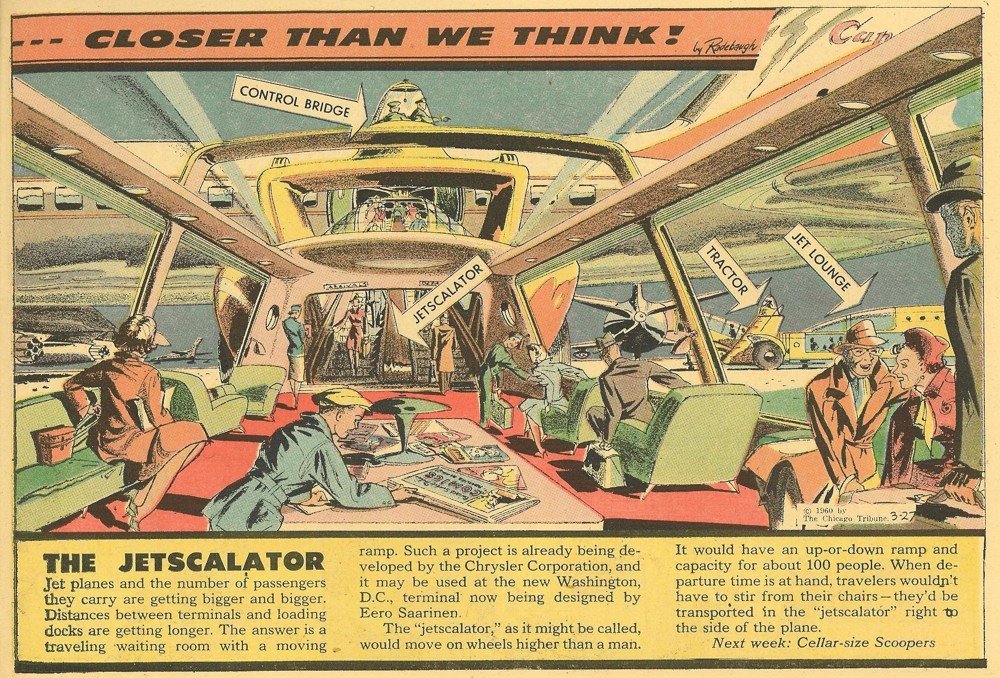

Arthur Radebaugh lived from 1906 to 1974 and built on his early career as an illustrator for Detroit-based advertising agencies to become a “funny-pages futurist,” producing the syndicated Sunday comic strip Closer Than We Think for the Chicago Tribune—New York News Syndicate from 1958 to 1963.

In this episode we meet Douglas M. Stewart Jr. and the other producers of Chesley Bonestell: A Brush With the Future, a 2019 documentary about Bonestell, as well as Brett Ryan Bonowicz, maker of Closer Than We Think, a 2018 documentary about Radebaugh. And we hear from veteran science journalist Victor McElheny, who lived through (and documented) the era when Bonestell and Radebaugh were offering their visions of space and the future.

The episode argues that futurist art, done well, can become a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy. It can teach consumer audiences what to want and expect—whether that’s moon bases or self-driving cars or talking refrigerators—and it can inspire at least few people to become the scientists and engineers who actually go out and build those things.

Not mentioned in this episode, but along similar lines, there’s an amazing new three-part documentary by Brett Ryan Bonowicz called Artist Depiction. It chronicles the work of three space artists—Don Davis, Charles Lindsay, and Rick Guidice—for NASA. It’s available now on Amazon Prime.

Trailer: Chesley Bonestell: A Brush with the Future

Trailer: Closer Than We Think

Gallery: Images by Chesley Bonestell and Arthur Radebaugh

Mentioned in this Episode

Boston Science Fiction Film Festival

Chesley Bonestell: A Brush With the Future (documentary website)

Closer Than We Think (Vimeo on-demand)

Closer Than We Think (original Indiegogo page)

Destination Moon (1950 trailer)

Ron Miller, Frederick C. Durant III, and Melvin H. Schuetz, The Art of Chesley Bonestell (Collins & Brown Limited, 2001)

Matt Novak, “Sunday Funnies Blast Off Into the Space Age,” Smithsonian Magazine, January 27, 2012 (an article about Athelstan Spilhaus’s Sunday comic strip Our New Age)

Paleofuture, a retrofuturism blog at Gizmodo by Matt Novak

Progressive Souls, a two-part episode of Ministry of Ideas

Soonish Episode 2.08: Sci-Fi that Takes Science Seriously

Soonish Episde 1.01: How 2001 Got the Future So Wrong

Chapter Guide

0:21 Under the Golden Gate Bridge

1:18 A Glimpse Into the Future

3:56 How Come I Never Heard of Chesley Bonestell?

4:37 Meet Arthur Radebaugh

6:45 Round Table Interview with Douglas Stewart, Christopher Darryn, and Kristina Hays

9:43 Mars as Seen from Deimos

11:50 Chesley Bonestell: A Brush with the Future Trailer

13:30 Destination Moon

15:13 Working with Wernher von Braun

17:03 Commercial Instinct

18:03 Romantic Rockets

20:20 Midroll Announcement: Support Soonish on Patreon

22:09 Brett Ryan Bonowicz

25:12 Influencing the Jetsons

26:21 Extremely Fast and Incredibly Closer Than We Think

29:54 Imagining Catastrophe

31:21 Conclusion: Competing Styles of Visual Futurism

32:45 End Credits and Announcements

Notes

The Soonish opening theme is by Graham Gordon Ramsay.

All additional music is by Titlecard Music and Sound.

If you like the show, please rate and review Soonish on Apple Podcasts / iTunes! The more ratings we get, the more people will find the show.

You can also support the show with a per-episode donation at patreon.com/soonish. Listener contributions are the rocket fuel that keeps this whole ship going!

Full Transcript

You’re listening to Soonish. I’m Wade Roush.

There’s a picture you may have seen painted from the point of view of Fort Point Rock, where San Francisco meets the Pacific Ocean.

In the foreground you can see the old brick and masonry fort from the 1850s. In the hazy background you can see the headlands of Marin County. And towering above the fort, half shrouded in fog, is the shining and ethereal Golden Gate Bridge.

The painting is incredibly evocative, especially if you’ve been to this exact spot and seen this view. Looking at it, you can almost feel the cool mist on your face and hear the surf and the booming echoes of traffic on the bridge.

There’s just one thing about this painting that’s a little bit unusual.

It’s from 1933.

The Golden Gate Bridge wasn’t finished until 1937.

So, when this painting was created, it was a glimpse into the future.

The man who painted it was named Chesley Bonestell.

In 1933 Bonestell was working in the office of Joseph Strauss, the chief engineer for the Golden Gate Bridge project.And his job was to translate the technical blueprints into renderings that would explain to the public exactly how this massive structure, priced at half a billion dollars in today’s money, was going to be built.

Basically, if you were a taxpayer or a bond investor or a highway commissioner in northern California, then… Bonestell had a bridge to sell you.

And that’s exactly what he did.

Bonestell’s art for the bridge commission fueled the investment and public enthusiasm that kept the project going all the way through the Great Depression.

And what’s largely forgotten now is that the Golden Gate Bridge existed as an imaginary object for years and years before it was actually built.

And the imaginary vision owed everything to the work of artists like Chesley Bonestell.

I’ve said this before here on the show, but the future doesn’t exist. It’s always just a picture in our heads. Until it actually arrives. And then it’s the present. And then we need a new picture.

Today I’m going to talk about two illustrators who supplied that picture for millions of people during a critical period in the middle of the 20th century, when so much of the world we take for granted now was being built.

Bonestell is one of them. After his work for Joseph Strauss, he went to Hollywood and became the movie industry’s highest-paid maker of matte paintings for backdrops.

Do you remember the Xanadu mansion from Citizen Kane? That was a Bonestell painting.

But even before World War II was over, Bonestell started to think bigger.

He wondered what kinds of views we might see when we started to send rockets to the Moon and the outer solar system.

His space art reached the public through magazines like Life and Collier’s and on the covers of science fiction magazines.

And he not only taught people to expect what the surface of the Moon or Mars might look like, decades before we actually went to those places; he also worked directly with space age pioneers like Wernher von Braun.

And his renderings of distant planets and futuristic spaceships stimulated generations of young people to go into astronomy or astronautics.

If some of his paintings look a little dated today, it’s because they inspired scientific discoveries and engineering innovations that went way beyond what even he could imagine.

But very few people today even know his name.

Doug Stewart: I have heard this quite a few times. People say, ‘How come I never heard of this man?’ And the reason is, the reality ultimately met the fantasy. The reality of what the space program yielded kind of became more exciting than Chesley's work.

That’s Douglas Stewart. He’s the director of a new documentary called Chesley Bonestell: A Brush With the Future.

Doug Stewart: So our mission here is to connect with the the public with this wonderful man who really you could say he's the man who helped get us to the moon with a paintbrush.

The other illustrator we’ll meet in today’s episode is also the subject of a recent documentary. His name was Arthur Radebaugh.

And he wasn’t as well known as Bonestell, but he probably reached just as many people through his Sunday newspaper comic strip, Closer Than We Think.

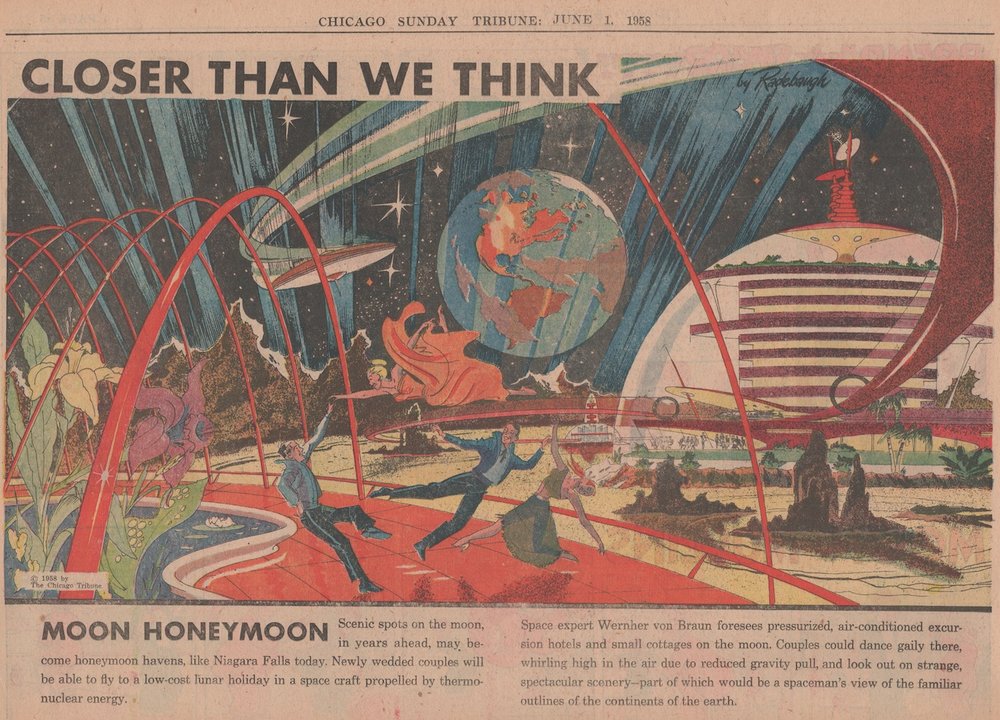

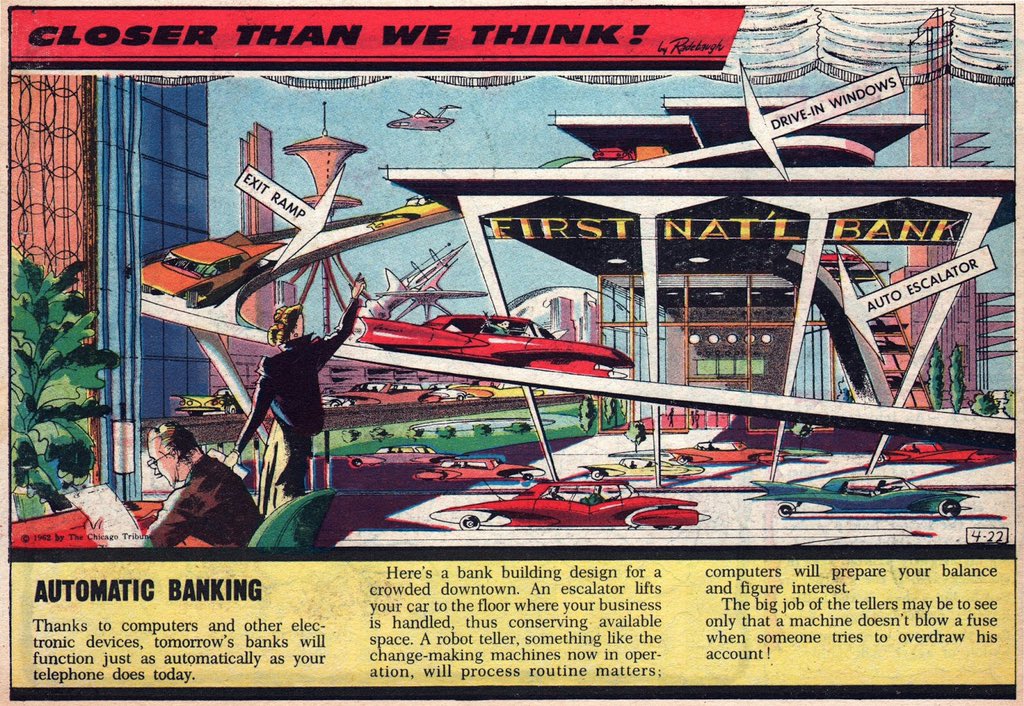

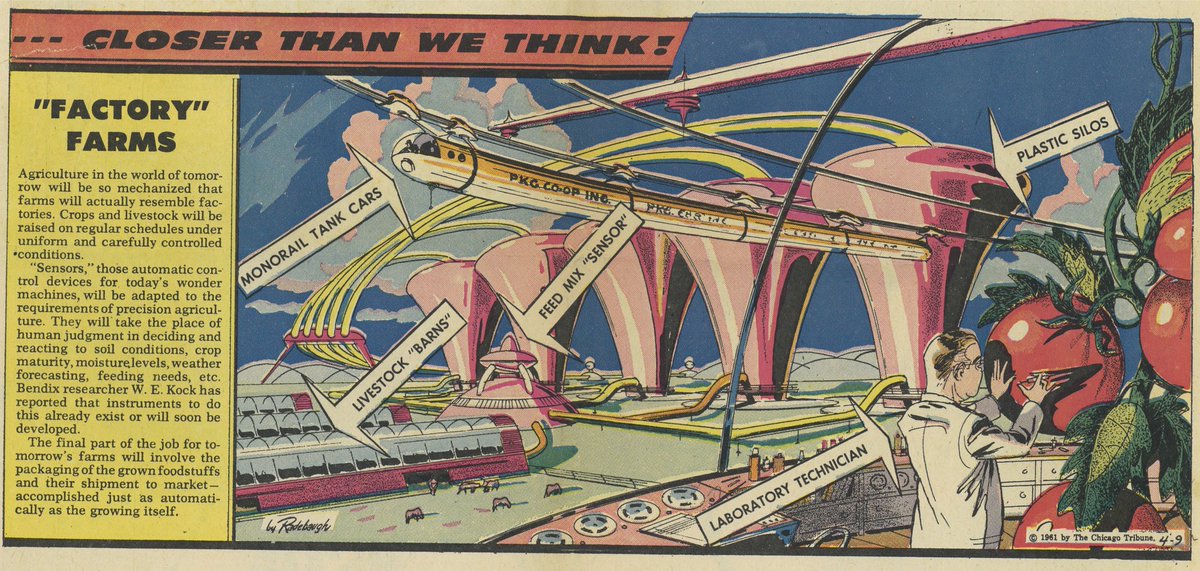

Every week Radebaugh’s comics gave readers of the funny pages a look at the real technologies they could expect to see in the future, from organ transplantation to robotic farm tractors to vacations on the moon.

Radebaugh himself started out as an illustrator making ads for car companies in Detroit, but after Sputnik he reinvented himself as a kind of herald a for the high-tech he saw coming just around the corner.

Brett Ryan Bonowicz: Looking at the way that his art changes you know post-World War II and the way that he moves from… illustration for car advertisements to you know doing Sunday funnies is an interesting thing to see the optimism come through….it’s like the perfect microcosm to kind of explore retro futurism.

That’s Brett Ryan Bonowicz, the director of the Radebaugh documentary.

Brett Ryan Bonowicz: People needed hope. People needed optimism. And I think that that's what they were getting through something like Closer than We Think.

Bonestell and Radebaugh weren’t always on-target with their predictions, and when we look back at their work now, it’s easy to focus on the things they got wrong.

And we’ll talk about a few of those later. But I think it’s more fun to look at what they got right.

And when you do that, you start to realize how influential these guys were.

It’s hard work making art that depicts the future in a believable way.

But if you do it as well as Bonestell and Radebaugh did, your work has a shot at becoming a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy.

It can teach people what to want and expect, whether that’s moon bases or self-driving cars or a talking refrigerators.

And it can inspire at least few people to become the scientists and engineers who actually go out and build those things.

Wade Roush: How about if we start with the formalities. Can I ask you to just basically introduce yourself in a line or two.

Doug Stewart: Hi I'm Doug Stewart. I also go by the screen title name there of Douglas M. Stewart Junior. I am the producer writer director of Chesley Bonestell, A Brush with the Future.

Christopher Darryn: My name is Christopher Darryn, I'm the associate producer of Chesley Bonestell, A Brush with the Future

Kristina Hays: Hi, my name is Kristina Hays. I'm the co-editor of Chesley Bonestell, a brush with the future.

Wade Roush: Okay, so tell me a little bit more about Chesley Bonestell the man. Who was this guy?

Doug Stewart: Well, Chesley was an artist first and foremost and that was his natural gift. And he used that gift to become an architect and to also go back to his talents as an artist to be able to paint extraordinary visions of the future. Now Chesley's career covered a great many historical events. He was, he helped design the Chrysler Building in New York City. He worked on the Golden Gate Bridge. He became a matte painter in Hollywood. Among the films that he worked on were Citizen Kane, The Fountainhead, Destination Moon and then reverting back to his artistic paintings he created a whole series of visions of what it looked like at least what he thought. So at the time using the best technology available what was he like to visit other planets like Mars for example the moons of Jupiter to look at Saturn from one of the moons. And he did a series of paintings that were published in Life magazine in 1944 and they really caught the country by storm. The country was really tied up in a very long painful experience with World War Two and Chesley his paintings gave a vision for the future of what what Americans could do after the war.

Now, even if you think you’ve never seen a Chesley Bonestell painting, you probably have, in a museum or a movie.

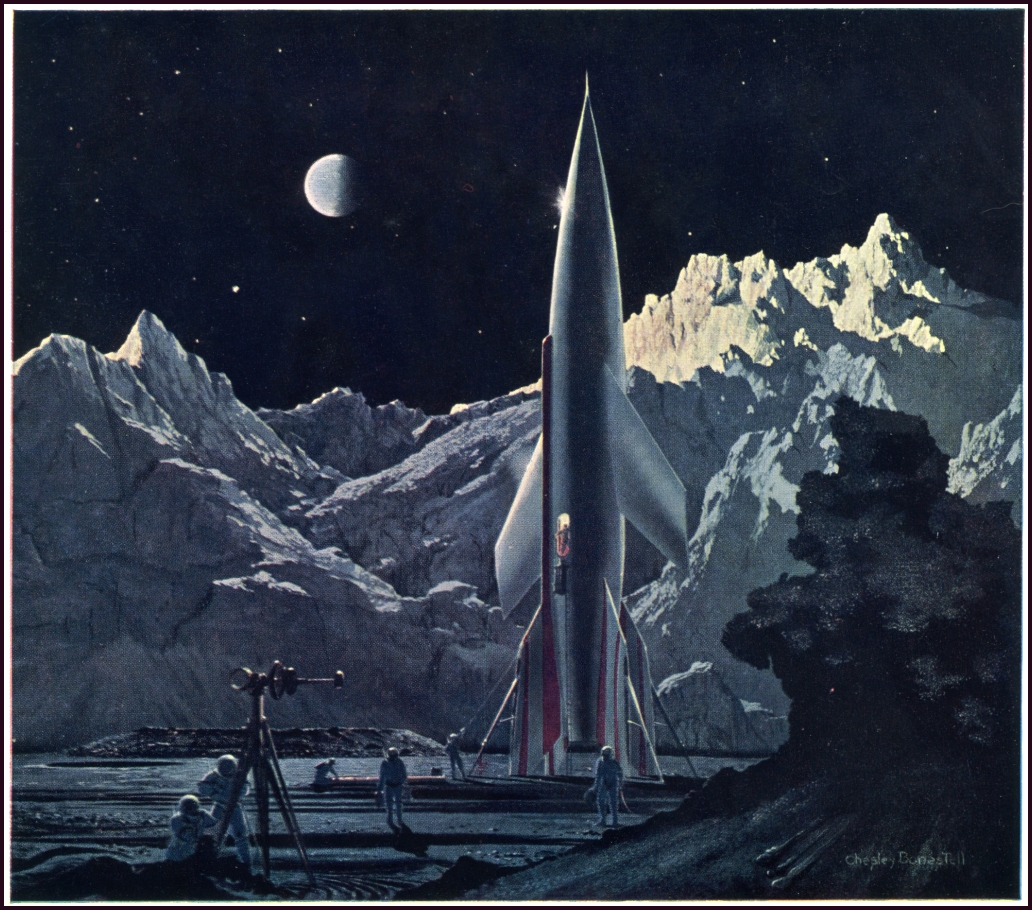

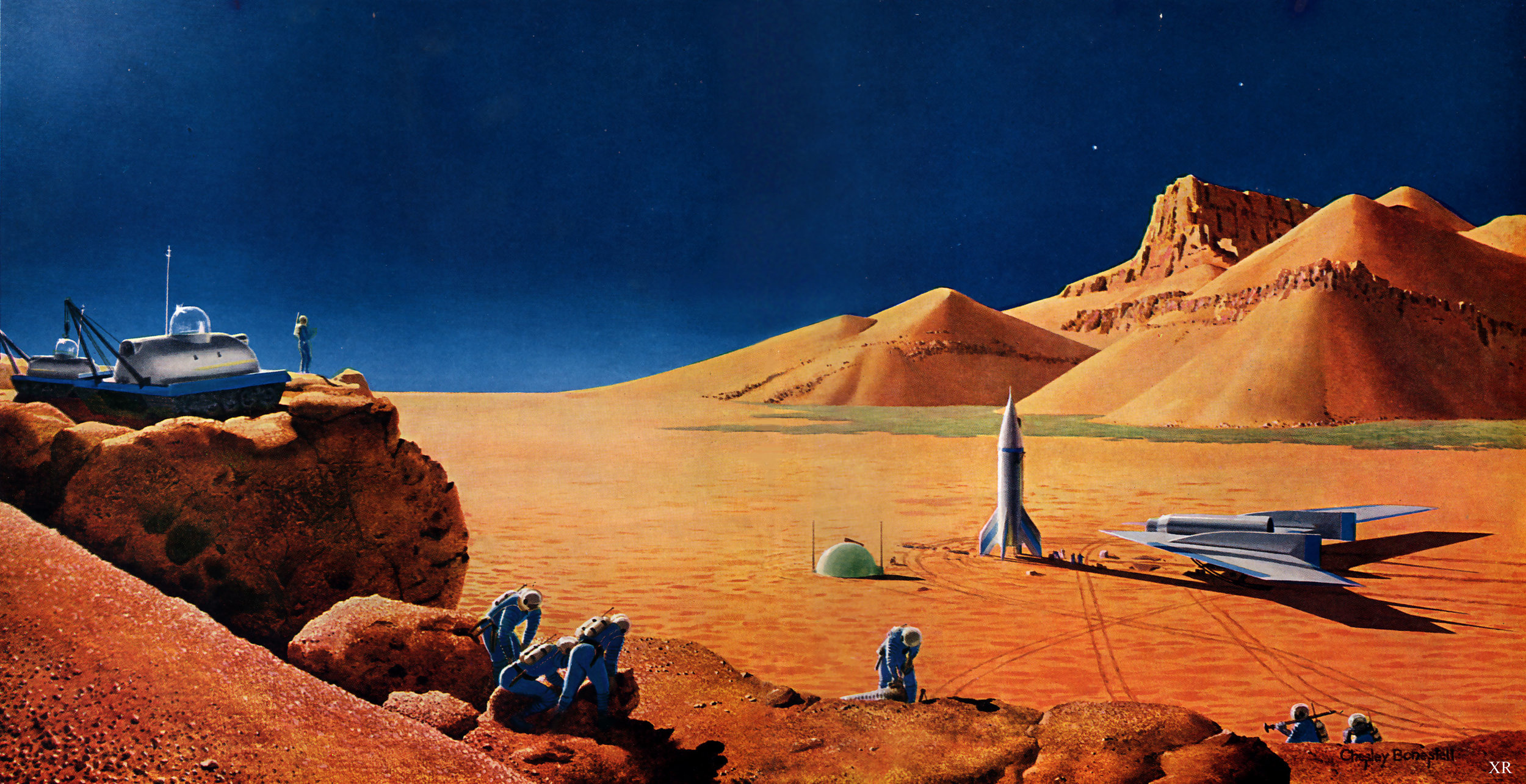

Long before anyone left Earth, Bonestell was making these highly detailed views of the ships we’d build to go to the Moon and other planets, and what we’d see when we got there.

Doug Stewart: There is a magical quality to these paintings. They look almost like photographs, people have said. And to a certain degree that's true. What makes a Bonestell painting unique to me is that you can. You can look at it. It's it's almost haunting and quality. But then when you go up to it there's and look at it very closely. There's a whole nother world there.

Christopher Darryn: Doug said it so well, I mean it's the photographic quality of the paintings that's so awesome to look at and you go wow if you knew you knew already you hadn't been there for real but you looked at the picture and you went wow you could almost convince somebody that you had been there.

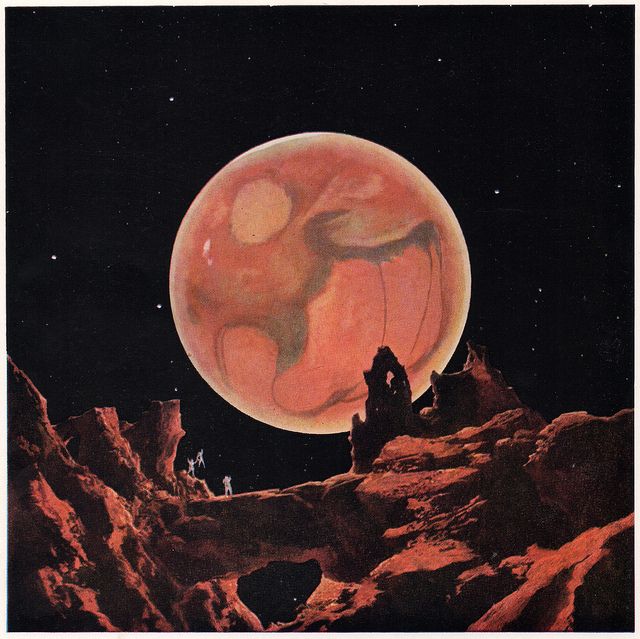

Kristina Hays: Actually I think I can talk about a specific painting.

Wade Roush: Sure. Which One?

Kristina Hays: “Mars as seen from Deimos, its Farther Moon.” In the foreground there is the craggy structures of the moon deimos. in the background is the red planet Mars and on the craggy foreground of the moon demos, there are three teeny tiny astronauts … one of the astronauts is jumping up towards the red planet Mars as if he's, It's almost as if he's trying to touch it, to reach out and touch it. It speaks a lot to the idea of men jumping out into this unknown territory.

Bonestell’s most famous painting shows Saturn as seen from the surface of its moon Titan.

It’s part of a collection that he sold to Life Magazine in 1944, for the astronomical fee, pun intended, of $30,000. That’s almost half a million in today’s money.

Doug Stewart: That painting is called the painting that launched a thousand careers because young people looked at that painting and they said that's what I want to do for a living. That's where I want to go. I want to I want to be there in outer space. And that's basically how the aerospace industry came to be formed by people who got something that magnetized energized that that didn't just lit up their idea of how exciting the future could be.

Now it turns out that Bonestell’s beautiful view of a gigantic Saturn looming in the sky above Titan’s craggy surface is technically impossible. Titan is actually shrouded in a thick haze of nitrogen and hydrocarbons. So, from the surface, you wouldn’t be able to see anything.

But we didn’t know that until the Voyager probes flew by Saturn and its moons in the early 1980s.

What really counted about these paintings from the 40s was just the idea that someday we’d be able to go to these exotic places.

Which, of course, we did!

Here’s a clip from the trailer for Doug Stewart’s documentary.

Ben Heywood: Chesley Bonestell was an artist who with his paintbrush with his paintings was able to show an entire nation that the conquest of space was not only possible but it was something that could happen within their own lifetimes.

Don Davis: His paintings helped inspire many people who were involved in the space field not just artists but many engineers, people who were helping to get us to the moon one day. Practically all of them would have been able to tell you who Chesley Bonestell was.

Rocco Lardiere: When you look at Bonestell's paintings there is an excitement designed into them. You look at the colors and you look at the shapes you look at the beauty. You say I want to go there and I want to see that.

David Aguilar: Whoever steps foot onto the surface of Mars for the first time will see a vista, will see a beauty, will see a world that was brought to us by Chesley Bonestell decades before.

Those were the voices of museum curator Ben Heywood, space artist Don Davis, rocket engineer Rocco Lardiere, and astronomer and space artist David Aguilar.

The film isn’t out on DVD or streaming platforms yet, because it’s still making rounds at film festivals.

I saw it at the Boston Science Fiction Film Festival, where it won the award for best documentary.

Now, there’s a little bit of irony in that award, since Bonestell himself claimed that he didn’t like science fiction.

He always tried to model his views of spaceships or the surfaces of distant planets on the best actual science he could find.

But he also knew which side his bread was buttered on.

The editors of science fiction magazines were always willing to buy his paintings for their covers.

And in 1950 Bonestell created the matte paintings for a movie called Destination Moon, which inspired a whole generation of moviegoers and filmmakers with its groundbreaking special effects.

Doug Stewart: I read an interview that Steven Spielberg did for TV Guide. He said the first science fiction film I ever saw was one that my father took me when I to when I was five years old. And that was Destination Moon.

[Audio clip from Destination Moon]

Now I’ve talked before on the show, back in Season 2, Episode 8, about the golden age of hard science fiction, from the 1940s to the early 1970s.

That was a time when a lot of science fiction authors and filmmakers were doing their best to stick to the known laws of physics.

Under the rules of hard science fiction, you could show things that were futuristic, but not things that were outright impossible.

And that meant that the membrane between science and science fiction was a little more…leaky than it is today.

There were people like German-born rocket scientist Wernher von Braun and science writer Willy Ley who weren’t ashamed to use a little bit of science fiction to generate public enthusiasm for their ideas about space travel.

And illustrators like Bonestell were there to help them do that.

Von Braun and Bonestell met in 1951 at a conference in Texas on the medical aspects of space travel.

Even before he helped the Nazi government develop the V-2 rocket, Von Braun had started imagining the kinds of rockets and spaceships that would be needed go to the Moon and Mars.

After that Texas conference Von Braun showed his sketches to Bonestell. And they began a collaboration that led to a series of eight illustrated articles about the future of space exploration publishd Collier’s magazine between 1952 and 1954.

Here’s how space artist Ron Miller described those articles in his 2001 book about Bonestell.

Wade Roush Voiceover: These magazines hit the American public of fifty-odd years ago like a bombshell. Until their appearance, the whole concept of spaceflight had been something relegated to the far future, if not the stuff of science fiction. What von Braun and his team and done was show that, given enough manpower and money, spaceflight could be accomplished with the science and technology available in the early 1950s.

But they couldn’t have done that without Bonestell’s precise and persuasive illustrations.

Doug Stewart: Well he took the same [00:10:00] talent that he had when it came to architectural renderings and turning them into something that people could appreciate and understand. And he worked with Willy Ley and Werner von Braun. ….And he could take their complicated formulas and again do his magic of presenting what the future could look like if we decided to go and investigate and explore the final frontier meaning space.

Just three years after the Collier series was published, Russia launched its Sputnik satellite, and American space exploration bloomed from an idea in a magazine into a huge line item in the federal budget.

So in a way, Bonestell was like a lieutenant colonel in the advance guard for the public relations battalion of the US space program.

Victor McElheny: Bonestell himself had an unbelievably mature commercial instinct where the influence was in the media.

That’s Victor McElheny. He’s a retired science journalist who got his first science writing job in 1957 and went on to cover the Apollo program for the Boston Globe.

Victor McElheny: He understood that magazines like Life and Look and Colliers were, The Saturday Evening Post also had this…but he understood where something really dramatic that would be mind changing and give people an imaginative grasp of what it might be like. He had that sense and so apparently did von Braun… and the clear idea was to capture popular imagination to give a sense or some sense of the immensity of what would be possible.

Now, if you look at Bonestell’s paintings of Moon and Mars rockets from the 1950s, you’ll notice that they all look like giant stainless steel bullets with giant fins and wings. Frankly, they look a lot like von Brauns’ V-2 rockets from the 1940s. And even today that’s what every kid’s crayon drawing of a rocket looks like.

But that’s not the direction NASA took in the 1960s,

And it wasn’t long before the facts of space exploration totally outpaced the forecasts from Bonestell’s magazine spreads.

If you talk to the team behind Doug Stewart’s documentary, you’ll hear a couple of different ways of looking at that.

Kristina Hays: Chesley's paintings of rocket ships look nothing like the Saturn V. They looked nothing like the Redstone rocket. Like, if you were to actually go into the atmosphere with those big wings, they would almost certainly burn off. That vision is now is romantic now and old fashioned. It took a while to realize that in space you don't need wings you just need a tube in order to go into space. But it still doesn't deny, it still doesn't negate the impact that he had at the time on the American public.

Christopher Darryn: I see it this way. Let's look at the SpaceX, the new starship. It's stainless steel. It looks very much like Chesley Bonestell's drawings. So a lot of times when people say well Chesley’s spaceship doesn't look like they do now. Well we're not done with the future yet. We don't know what they're going to look like 10 or 20 or 30 years from now. So I don't see Chesley as being wrong in these spaceship designs. I just see that the future has not played out yet. And he just hasn't had the time to be right.

That was Kristina Hays and Christopher Darryn again.

And I kind of love that last idea from Darryn. It could be the universal slogan of futurologists.

“I’m not wrong. I just haven’t had time to be right.”

It might be true of Bonestell. And in a minute we’ll see how that idea played out in the career of his contemporary, Arthur Radebaugh.

But first, a quick break.

[Midroll announcement]

Hey, I don’t do this very often here at Soonish, but I wanted to take a minute to remind you that this is a listener-supported show.

Thousands of people download every episode, and somewhere between one and two percent of you sign up to support the show with a per-episode donation at patreon.com/soonish.

Which is really great, because that money goes a long way to cover costs like editing software, recording equipment, and music licensing.

But over time, I’d love to bump up the percentage of listeners who become members, so that I can take this part-time podcasting job and grow it into something closer to full-time.

And right now I’ve got a special limited-time offer for you. If you go to Patreon.com/soonish and sign up at the $5 per episode level or above, I’ll send you our most popular piece of swag, the Soonish coffee mug.

It’s got the new Season 3 logo on one side and the show’s motto on the other side. But the mug will only be available at the $5 level until June 8th 2019. After that the mug will move up to the next reward tier, and it’ll only be available to folks contributing $10 per episode or more.

In fact, starting June 8 I’ll be refreshing the rewards available at every level.

The countdown to that June 8 deadline is underway, so I hope you’ll sign up now at Patreon.com/soonish.

There are no paywalls here at Soonish. But I know that you know that the show isn’t free to make.

And the fact that there are listeners out there who want to contribute—well, that’s like rocket fuel that keeps this whole thing going.

So get on board at patreon.com/soonish.

[End of midroll announcement]

So I mentioned before the break that Chesley Bonestell: A Brush With the Future won the best documentary prize at the 2019 Science Fiction Film Festival here in Boston.

Who won the 2018 best documentary prize, you may ask?

Well, it was Brett Ryan Bonowicz, the director of Closer Than We Think, a documentary named after the weekly comic strip by Arthur Radebaugh that reached millions of Sunday newspaper subscribers between 1958 and 1963.

Here’s part of my interview with Bonowicz.

Wade Roush: For the benefit of people who have not yet seen your documentary, who was Arthur Radebaugh?

Brett Ryan Bonowicz: So Arthur Radebaugh was an illustrator that lived in Michigan. You know obviously being in Michigan a lot of his career and a lot of where that money was in illustration was in advertising at that time. And then after World War Two it becomes more of what we now look at as this retro future style and he has a few different syndicated strips in newspapers one of them being Can You Imagine and then another one called Closer Than We Think. And Closer Than We Think would make a prediction. Every week in the paper of you know a certain invention or a way that your life was going to improve or you know it could be a small object like a wristwatch TV or a big idea like having your honeymoon on the moon.

Wade Roush: you spent so much time immersed with these strips. I'm wondering whether you have any special favorites?

Brett Ryan Bonowicz: Yeah absolutely. The one that I'm drawn to again and again and I've already mentioned, is “Moon Honeymoon.” So within that strip you know creating the picture in your mind that you know like you have this beautiful view of the earth. So you know you're on the moon, and you're having this honeymoon in the picture. There are only like four people there. So just imagining the economics of this, it's insane. It just doesn't really exist. There's four people that had to have paid a billion dollars each to have this honeymoon on the moon. There are these these brilliant structures, these kind of winding almost UFO-looking monorails going by. There's a lot of movement. There's trees and rocks under a dome. It's such a vibrant image of the future. It always catches me. I love this image for its optimism.

Brett Ryan Bonowicz: You know, his style is very obviously influential on something like The Jetsons. So like if you think about the Jetsons and then look at Radebaugh's work you can you can see a lot of ties.

Wade Roush: In things like the streamlined vehicles and the space age you know cars and you know flying saucer high rises and things like that?

Brett Ryan Bonowicz: Right. I think Matt Novak talks about this in the filrm, that Radebaugh was very genuinely talking about these ideas. They weren't meant to be kind of parody or jokes. The Jetsons—and this is something that people have forgotten in time—the Jetsons was a parody of everything that was going on you know in the early 60s.

Wade Roush: Right. I mean by that time these ideas have been around long enough that you could make a cartoon for prime time TV and and everybody was kind of in on the joke right. …but it only became a cliche in a way thanks to the sincere efforts of futurists like Radebaugh.

Brett Ryan Bonowicz: Yes absolutely. He was doing these things. because of you know this feeling in his own heart of what the future was going to be like.

Now back in the very first episode of Soonish I talked about the idea that there was something special about the century from 1870 to 1970, and especially the second half of that century, from 1920 to 1970.

That was the period when nearly all of our critical technological systems were being built, from the electrical grid to the highway system to aviation to the pharmaceutical industry.

So in a way, a Sunday comic strip about monorails or moon honeymoons was just a reflection of what was going on in the larger culture.

At the pace things were changing, Radebaugh didn’t have to see all that far ahead to imagine things like electric vehicles or space telescopes.

Here’s veteran science journalist Victor McElheny again.

Victor McElheny: So you know things do go awfully fast. You're on several tracks right alongside each other. You're doing open heart surgery using a machine invented by a guy named Jack Gibbon. We've had the penicillin. We've had medical miracles. We've had the saving of a child with Rh rejection problems where you do the total blood transplant transfusion in order to save the life of the blue baby. You had miracles of the sort that were going on in the operating room in your own city. The takeoff for the moon on July 16th 1969—Lyndon Johnson is there. The politician who had more to do with actually making Apollo happen than than any other politician. And right near him is Charles Lindbergh. And that's 1969. That's forty two years after the 33 hour journey. So you're surrounded by new manifestations of modernity that appear miraculous that are happening extremely fast.

Closer Than We Think had a competitor called Our New Age, by a South African oceanographer named Athelstan Spilhaus, which ran in almost a hundred newspapers starting in 1957.

And both comics were part of a bigger push in the post-Sputnik era to use popular media to do what we’d now call STEM education.

Victor McElheny: That’s another thing. I mean, it was it was understood I think all automatically by people in late 1950s, in 1957, that the key group was to get young willful auto didactic children to [00:59:30] step forward and do science rather than something else.

The point of Radebaugh’s Sunday comics wasn’t necessarily to achieve high accuracy.

Brett Ryan Bonowicz: His batting average is like pretty ok if you stretch it a bit. Moon Honeymoon, I don't think we're anywhere near. But then you know you have things like the “Visiphone” where you're like, this is kinda like FaceTime and Skype. But looking at him as an actual like prognosticator, I don't know how much higher his average would be than someone else at that time just spewing out two hundred ideas about the future.

The ideas were the whole point. Radebaugh was trying to simultaneously entertain people and get them excited about science and technology.

Now there’s one thing you definitely won’t get from Radebaugh’s comics, and that’s any sense of the risks and costs that go along with rapid technological change. The strip was relentlessly optimistic. So there aren’t any drawings of traffic jams or pollution or mass surveillance.

And on that score Chesley Bonestell was a little bit less cheerful than Arthur Radebaugh.

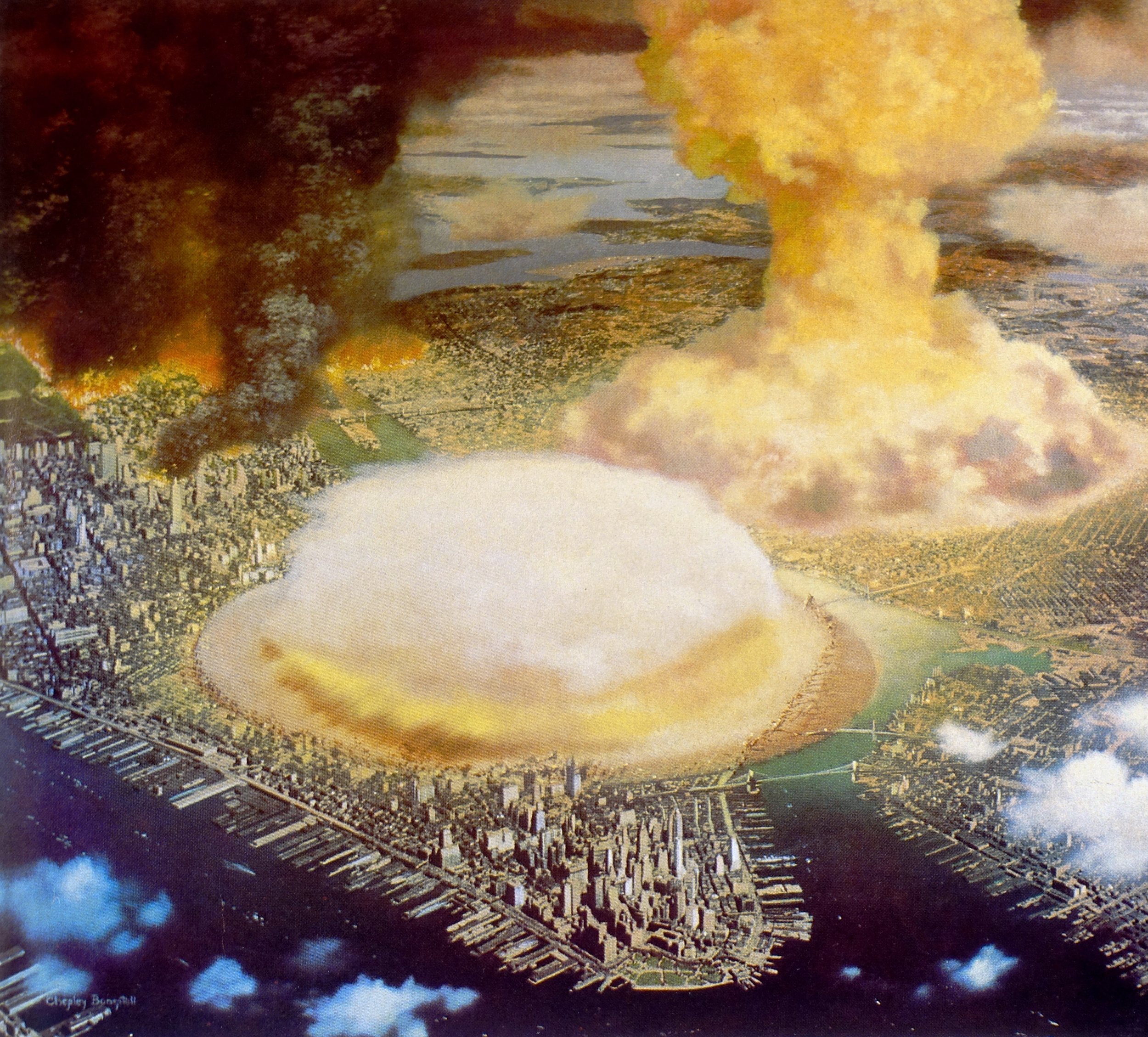

In 1948 Collier’s magazine asked Bonestell to imagine what a nuclear attack against the United States might look like. He painted a brutally convincing image of an atomic blast flattening midtown Manhattan and mangling the Williamsburg Bridge.

Doug Stewart: Chesley was there in the 1906 earthquake of San Francisco. He saw the whole city destroyed … there was a connection between Chesley’s personal experience in that catastrophe and the pending catastrophe or proposed catastrophes that could lie ahead for the earth including the atomic bomb. And there Chesley has a whole series of atomic bomb paintings that are quite realistic and quite frightening in their own right.

What was different about Bonestell’s atomic bomb paintings is they weren’t necessarily meant as forecasts. They were more like talismans, intended to ward off the specter of nuclear destruction.

The idea was to make atomic weapons look so destructive that no politician after Harry Truman would ever use them in anger again.

And so far, it’s worked.

Which brings us all the way back to the beginning.

If you’re a futurist working in a medium like painting or comics or film, you can use your art to inspire people, or to scare people, or both.

You can create bridges. And you can destroy bridges.

The question is, what’s the right balance between these two impulses?

After people like Bonestell and Radebaugh left the scene, what you might call visual futurism took a much darker turn, and dystopias began to pervade popular culture.

You know, I’m talking about Planet of the Apes, Mad Max, Escape from New York, The Matrix. And every single Ridley Scott film, except for The Martian in 2015.

I like those movies, and dystopian art can be compelling in its own way.

But dystopias don’t make anyone say, “Hey, I’m going to build a rocket to Mars,” or “Hey, I’m going to create a vaccine for cancer.”

Our challenges today aren’t like Sputnik. They’re much more real.

So maybe future generations are going to need their own Chesley Bonestells and Arthur Radebaughs.

Artists who understand that you have to be careful what you paint. Because you might just get it.

Soonish is written and produced by me, Wade Roush.

Our theme music is by Graham Gordon Ramsay.

And all of our other music is from Titlecard Music and Sound in Boston.

You can check out art by Chesley Bonestell and Arthur Radebaugh and watch trailers for the two documentaries at our website, soonishpodcast.org.

Soonish is a proud founding member of Hub & Spoke, a Boston-based collective of smart, idea-driven podcasts.

And this week I want to let you know about the magnificent two-part season 2 closer from Ministry of Ideas.

It’s a two-part episode about how Christian denominations in America used to play an important role in socially progressive movements, and how they forfeited that role, and how they might just win it back.

You can listen to both parts of that episode at ministryofideas.org.

Special thanks to our top supporters on Patreon, including Kent Rasmussen, Celia Ramsay, Jamie Roush, Paul and Patricia Roush, Victor and Ruth McElheny, and Warren and Lucia Prosperi.

And thank you for listening. I’ll be back with a new episode….Soonish.